we can create space in the seemingly solid flow of existence

Art of Becoming, No. 64

Whole intellectual industries are devoted to proving that there is nothing new under the sun, that everything comes from something else—and to such a degree that one can never tell when one thing turns into something else. But it is the moment when something appears as if out of nowhere, when a work of art carries within itself the thrill of invention, of discovery, that is worth listening for. It’s that moment when a song or a performance is its own manifesto, issuing its own demands on life in its own, new language —which, though the charge of novelty is its essence, is immediately grasped by any number of people who will swear they never heard anything like it before—that speaks. In rock ’n’ roll, this is a moment that, in historical time, is repeated again and again, until, as culture, it defines the art itself.

-Greil Marcus, The History of Rock ’n’ Roll in Ten Songs

The most radical innovations in art and music emerge not through solitary genius but collective becoming—a truth crystallized in Buddhism’s principle of pratītyasamutpāda, or dependent origination. This philosophy reveals creativity as a dance of interconnected causes: every flash of brilliance arises from conditions seeded by predecessors, collaborators, and cultural ecosystems. What we perceive as spontaneous rupture—Elvis Presley’s primal yelp on “That’s All Right,” Jimi Hendrix’s incendiary fretboard pyrotechnics—is in fact the flowering of invisible networks. Like mycelia threading through forest soil, dependent origination weaves past and future through subterranean connections, transforming apparent voids into fertile ground for revolution.

Rock ’n’ roll’s history pulses with this truth. Presley’s 1954 breakthrough distilled Memphis blues, Appalachian folk hymns, and Pentecostal fervor into a sound that rewrote popular culture. Yet under dependent origination’s lens, his “originality” becomes a mosaic of co-arising influences: T-Bone Walker’s jazz-blues riffs migrating through Chuck Berry’s country-twanged guitar, Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s gospel virtuosity electrifying working-class juke joints. These artists didn’t invent—they rearranged, becoming mediums for the cultural unconscious. Les Paul’s tape loops, by allowing sound to replicate and mutate, literalized dependent origination’s premise: innovation emerges when existing elements interact under new conditions.

This alchemy of interdependence dismantles linear narratives of progress. The British Invasion refracted Mississippi Delta blues through postwar Liverpool’s industrial clang, while hip-hop transformed disco’s opulence into South Bronx streetcorner liturgy. Tibetan thangka painters, required to master centuries-old motifs before attempting innovation, mirror jazz musicians who absorb Ellington’s harmonies to fuel Coltrane’s free-form explorations. John Cage’s 4’33”—a composition of ambient silence—epitomizes dependent origination’s paradox: emptiness becomes form when we attend to the web of sounds already present. To innovate, these creators didn’t reject tradition; they deepened their dialogue with it, proving that novelty flourishes through communion rather than conquest.

The illusion of separateness dissolves under dependent origination’s gaze. David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust persona channeled Kabuki theater’s gender-fluid archetypes through glam rock’s glitter, while Beyoncé’s Lemonade wove Yoruba cosmology into trap’s digital thrum. Even punk’s snarling DIY ethos, seemingly antithetical to tradition, carried Delta blues’ raw immediacy into 1970s squat houses. As ambient pioneer Pauline Oliveros noted, “Deep listening is remembering the future”—an act of creative karma where ancestral echoes shape tomorrow’s vibrations. The trap producer warping an ’80s synth-funk sample becomes a node in samsara’s wheel, spinning old gold into new constellations. True originality arises when we surrender the myth of autonomy. The guitarist stumbling upon a revelatory chord progression shares the meditator’s epiphany: both glimpse the luminous interdependence beneath apparent solitude. Zen’s shoshin (beginner’s mind) mirrors the artist’s task—to approach materials with porous awareness, letting latent connections manifest. Dub reggae’s architects transformed silence into rhythmic architecture by subtracting rather than adding, revealing how absence too is woven into dependent origination’s tapestry.

So, we might reconsider innovation an act of reciprocity. The Velvet Underground’s feedback drones carried La Monte Young’s minimalist meditations into rock clubs, just as rave culture resurrected gospel’s ecstatic communion through synthesized beats. Every “new” genre is a palimpsest—Patti Smith’s punk poetry scribbled over Blakean prophecies, D’Angelo’s neo-soul baptizing Prince’s erotic theology in muddy river water. To create is to collaborate across time, midwifing forms that ancestors half-remembered and futures faintly hummed.

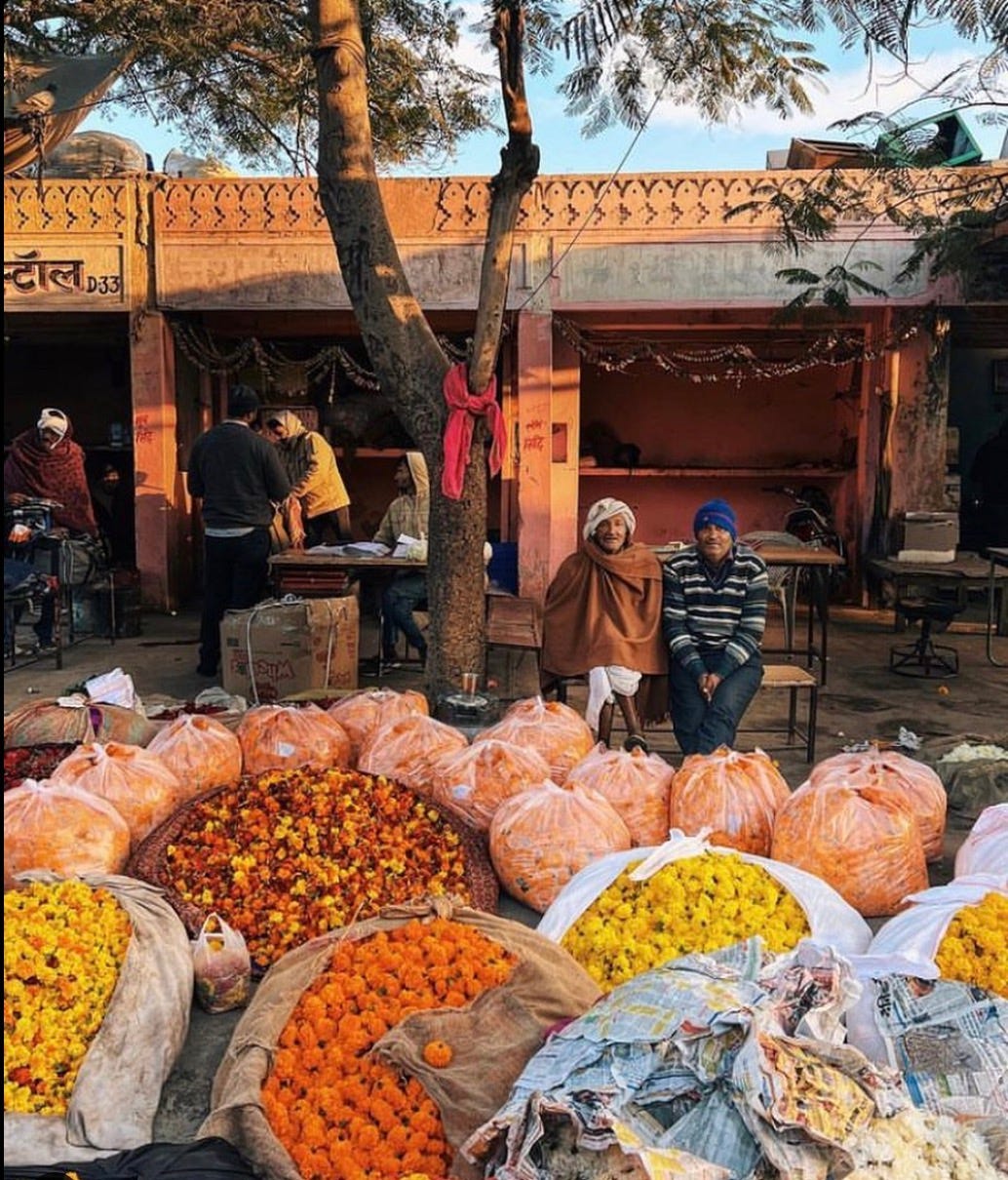

Today’s meditations on dependent origination might remind us that nothing self-originates, yet everything transforms. The artist’s role isn’t to invent but to notice—to trace the hidden threads between Memphis and Mumbai, between temple chants and turntable scratches. In doing so, we participate in culture’s eternal return: not repeating the past, but renewing its pulse in the present’s key. The revolution was never new; it was always here, whispering its songs through the world wide web.

Beyond Linear Causality (Dependent Origination)

A Dharma Talk by John Peacock

This practice could severely change your life. And it’s meant to; that’s exactly what it’s meant to do. It could actually change your life. But it takes time and it takes patience. And it takes the ability to open to, often, the painful in life.

Meditation Practice

Identify with precision and awareness the beginning and end of both the in-breaths and out-breaths. Pay close attention to the subtle transitions where each breath initiates and concludes, noting the specific sensations that mark these boundaries in your breathing cycle.