Previously, Week 10

Welcome to Week 11 of Art of Becoming.

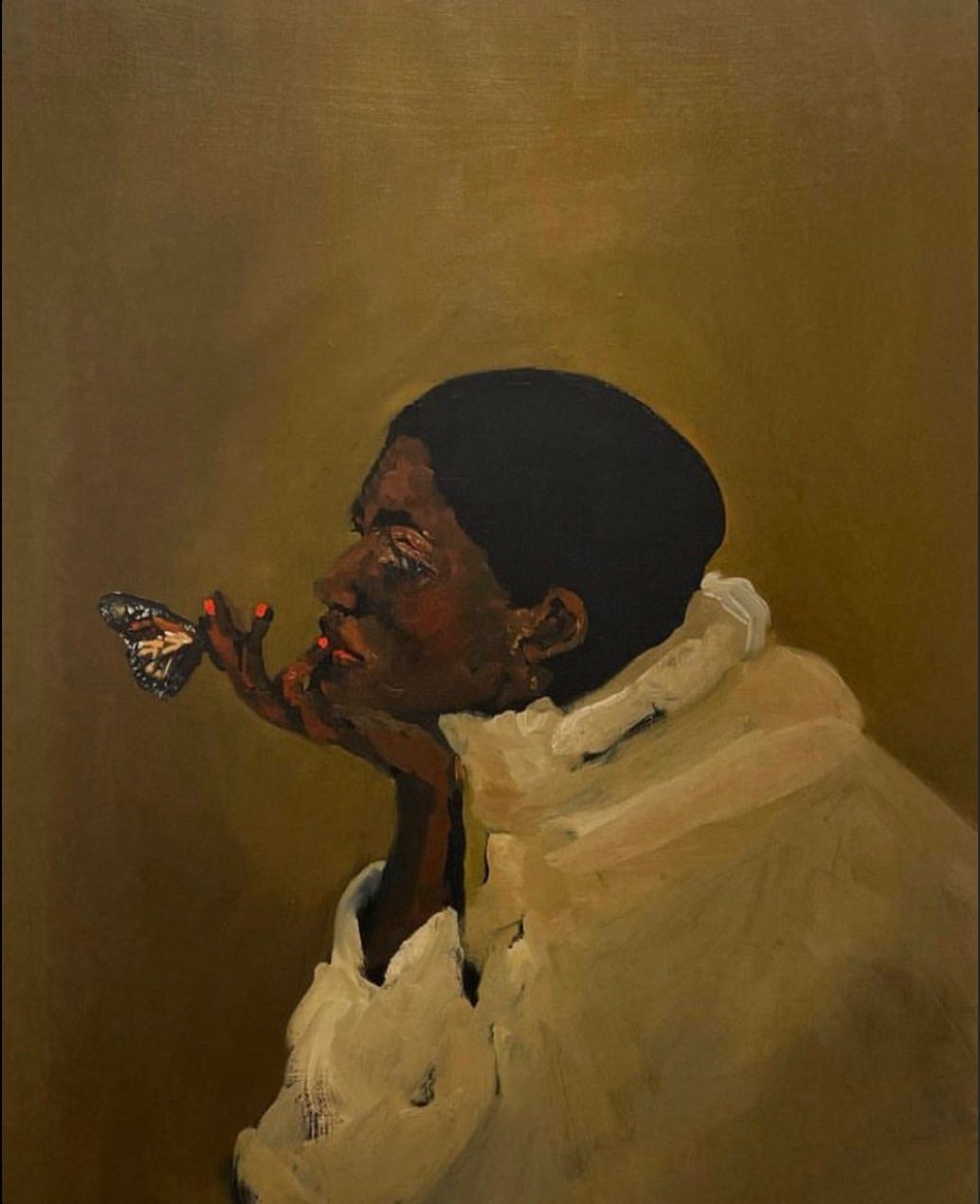

As we launch this seven-part contemplative series on sustainability, we begin not with carbon footprints or policy frameworks, but with the mind itself: the primordial forge where concepts like “sustainability” are born, refined, and ultimately embodied.

This opening contemplation invites us to explore the bedrock of all sustainability—how direct experience becomes language, and language becomes world. In the week ahead, we will traverse the outer dimensions of sustainability—climate, culture, cosmology—but today, we warm ourselves at the primal fire. How do raw sensations of wind on skin or the ache of loss crystallize into words like “stewardship” or “compassion”? How does the brain’s ancient survival circuitry learn to encode visions of collective thriving? This is the neuroscience of concept formation at its most visceral, a reminder that every paradigm shift begins as a synaptic spark.

It is, on the one hand, rash and unphilosophical to attempt to set limits to the ultimate power of man over inorganic nature, and it is unprofitable, on the other, to speculate on what may be accomplished by the discovery of now unknown and unimagined natural forces, or even by the invention of new arts and new processes. But since we have seen aerostation, the motive power of elastic vapors, the wonders of modern telegraphy, the destructive explosiveness of gunpowder, and even of a substance so harmless, unresisting, and inert as cotton, nothing in the way of mechanical achievement seems impossible, and it is hard to restrain the imagination from wandering forward a couple of generations to an epoch when our descendants shall have advanced as far beyond us in physical conquest, as we have marched beyond the trophies erected by our grandfathers.

-George Perkins Marsh, Man and Nature; or, Physical Geography as Modified By Human Action (1864)

In the restless dance between human ingenuity and Earth’s ancient rhythms, there exists a quiet intelligence—a primal, integrative knowing that murmurs through the synaptic firings of our neural networks…and the weathered pages of 19th-century treatises. To know the meaning of sustainability, I’ve learned, is to oscillate between two mirrors: one reflecting the outer landscapes we plunder, the other revealing the inner terrains we inhabit. George Perkins Marsh—diplomat, linguist, proto-ecologist—listened to this dialogue long before the word sustainability entered our lexicon. Born in a Vermont stripped of 75% of its forests during his lifetime, Marsh bore witness to what he called the spendthrift waste of nature’s bounty— a phrase that now echoes in Joe Loizzo’s studies of the brain’s traumatic avoidance patterns. Reading the source of today’s insight, Marsh’s Man and Nature (1864) reminds me that Marsh was putting forth not so much a treatise than a cipher. He was translating scarred slopes and eroded plains into a warning: We are not separate from the systems we plunder—we are the systems we plunder.

It’s remarkable, because Marsh was fluent in 20 languages and steeped in the philologist’s art. So, it seems only natural, of course, that he approached nature as a dying dialect. The denuded hills of the Mediterranean were not merely ecological wounds but lost verses in Earth’s epic poem—a text as layered as the Aeneid or the Metamorphoses, awaiting translation. When he wrote of humanity’s moral revolutions, he channeled a plea etched into modernity’s fragmented attention spans: To heal the land, we must first decipher the codes of our own cognition.

Centuries later, Loizzo’s work on neuroplasticity mirrors this intuition. The brain’s gamma wave activity—those bursts of neural lightning that rewire our habits—becomes Marsh’s “artesian fountains,” latent forces waiting to be tapped. And, the vagus nerve, with its capacity to calm the body’s stormy seas, finds its analogue in Marsh’s vision of heavy walls of masonry. In Man and Nature, he praised civilizations that redirected destructive floods into irrigation systems, writing: “inundations of flowing streams [are] restrained by heavy walls of masonry… torrents compelled to aid… in filling up lowlands”. These walls were not blunt barriers; they were adaptive systems that transformed flowing water into fertile silt, preventing erosion while nourishing soil. What unites this view of walls and gamma waves is a recognition that supports how we might see sustainability—not as a policy but a way of seeing—a dynamic interplay between the mind’s capacity for intelligent redirection and Earth’s capacity for regeneration.

So, the denuded hills and our fragmented attention spans share a common syntax—a grammar of erosion that writes itself equally into landscapes and neural pathways. To “read” this erosion is to use that primal knowing again, and to confront a primal truth. If scarcity is a story we tell ourselves, then today’s teachers tell us that abundance is as real as the latent potential humming beneath every synapse and watershed. Both are forces waiting to be harnessed, not through domination, but through attunement. One requires meditative focus to rewire the mind’s habits; the other, hydraulic engineering. And the principle in both cases becomes ever more clear: regeneration begins when we stop seeing ourselves as separate from the systems we seek to remembrance of.

Perhaps, the inner dinosaur of our stress-reactive brain—the amygdala’s primal alarms—is not truly an enemy to vanquish, but instead a threshold. In Peter Levine’s work on somatic experiencing, he teaches us that trauma, like erosive rains, is not a force to suppress but a surge to redirect. So, when we encounter terraced slopes, we might see them as a channeling mechanism for floods that are, like trauma energy, otherwise destructive. Levine’s methods—grounded in the body’s innate rhythm of pendulation between activation and calm—reveal how the energy, when met with mindful attention, can integrate into our body’s innate fabric of resilience. This is not metaphor, but mechanics: neuroplasticity studies show us that every moment of focused attention thickens the prefrontal cortex, much like root systems stabilize soil against erosion. The mind, like the land, thrives when approached not as a problem to fix, but as a living system to listen to—a truth Levine echoes in his emphasis on the body’s “felt sense” as a compass for healing.

Here, we find a paradox of sustainability: it demands we release the illusion of control while embracing radical responsibility. The same neural networks that spiral into anxiety over climate collapse can also ignite the compassion to plant forests. The same cultural habits that accelerate ecological debt can be rewired into rituals of care. There is an alchemical potential latent in awareness. In the act of recognition, of coming back into connection with knowing inner or outer landscapes, is a vote for the world we wish to inhabit.

So, we sit with this truth and in so doing, confront a question: What if sustainability is less about saving the planet and more about relearning reciprocity? Do you remember how the ancients spoke of Sophia, the wisdom that whispers through ecosystems and nervous systems alike? She does not tally carbon credits or measure gamma waves; she asks only that we soften the boundaries between self and soil, between breath and atmosphere. When we pause to feel the weight of a stone, the coolness of wind, or the ache of a habit we’ve outgrown, we touch this wisdom. It is here, in the quiet space of attention and humility, that the mind’s healing capacities begin to flow.

Today, consider this radical insight from both neural and ecological science: thresholds are porous. A mind trained to meet stress with curiosity softens the amygdala’s grip; a society that values rest over extraction slows the pace of planetary burnout. The future is not a distant abstraction—it is the sum of these synaptic and societal shifts, moment by moment.

And, as you move through your days, let this question linger: What if the “moral revolution” we seek begins not in grand policies, but in the quiet act of noticing—of seeing the mind’s erosion and the earth’s renewal as facets of the same prism? The answer, like sustainability itself, is not a conclusion, but a practice—one breath, one sapling, one neural connection at a time.

The Neuropsychology of Sustainable Happiness

A Lecture by Joe Loizzo

…the vision of the new mindfulness research is that the prefrontal cortex is a part of our brain that's capable of reaching deep into all of these older brain regions like the limbic system, and even through the vagal nerve into the brain stem, is able to integrate all of these older perhaps more reactive or primitive parts of the nervous system into a higher socially engaged…mindful compassionate, truly civilized brain.

Meditation Practice

Today’s Instruction: Sit Like a Mountain

Close your eyes. Settle into your posture—spine upright, shoulders relaxed, hands resting naturally. Let your awareness drop into the body. Feel the weight of your bones, the gravity anchoring you to the earth. This is your foundation: the mountain’s base.

Now bring attention to the breath. Notice the rise and fall of the chest, the coolness of air at the nostrils. No need to control it. Simply observe. With each inhalation, sense the mountain’s mass—the ancient granite of resolve. With each exhalation, release any tension clinging to muscle or mind.

Discomfort will arise. A tingling leg, an itch, a thought about tomorrow’s obligations. Let these sensations crash against you like weather on a peak. Notice how the mind instinctively tightens around them, as if bracing against a storm. Do not armor yourself. Instead, widen the lens of awareness. Feel the discomfort as a wave—momentary, insubstantial—while the mountain remains unmoved.

Neuroscience tells us that the amygdala’s alarm signals dissolve within 90 seconds if unmet by narrative. Your task is not to endure, but to disidentify. Observe the raw sensation of “ache” or “annoyance” without layering it with my pain or this shouldn’t be. See it as a pattern of neural firing, already fading.

When distraction pulls you into thought, return to the breath. This is the mountain’s rhythm: erosion meets bedrock, agitation meets space. Every return is a microact of neuroplasticity—strengthening the prefrontal cortex’s capacity to hold steady amid life’s storms.

End by resting in the afterglow. Note how discomfort, unmet, loses its charge. The mountain never conquers the storm; it outlasts it. So too, your resolve is not a force to muster, but a presence to inhabit.

Why this works: By grounding in the body’s immediacy, you bypass the brain’s default mode network—the storyteller that amplifies suffering. The mountain metaphor leverages the insula’s interoceptive awareness, merging sensory clarity with metaphorical resilience. Discomfort, like all neural phenomena, is ephemeral. Your practice is to be the space it moves through.